Did you know that Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam provided refuge to Jewish citizens during World War II? And that one of our professors back then and his students forged identity cards? You will learn more about these stories in the latest VU podcast – which also features walking tours of the various historical sites.

A podcast (including a walking guide) will be presented during Kuyper Week, as part of the Kuyper Anniversary Year celebrations. This podcast will include two new city walks right through the heart of Amsterdam. The first of these walks will take you along our University’s historic buildings, including the present-day Kleine Komedie theatre (a building that once housed a missionary church run by the Free Church of Scotland) and several stunning buildings located on Keizersgracht.

The second walk leads along various buildings and homes in Amsterdam’s city centre that have a historic connection to the Vrije Universiteit and World War II: what were some of the resistance sites, where did people lose their lives, and which VU employees hid Jewish fugitives in their homes? The podcast will also spotlight several people who sided with the German occupiers.

A preview of the ‘Waar de VU ooit begon – 1870-1900 – Een wandeling met Abraham Kuyper’ (The Vrije Universiteit and its Origins – 1870-1900 – A Walk with Abraham Kuyper’)

First lectures

Back in the 19th century, the present-day Kleine Komedie theatre still served as a church building: a missionary church operated by the Free Church of Scotland. When Kuyper founded the Vrije Universiteit in 1880, he had yet to find a university building – in fact, he did not even have access to a lecture theatre. Three lecturers from the brand-new university asked the Scottish missionaries if they could give their first lectures in the church. It turned out there was room in the attic, so they were given the go-ahead.

The VU was just a small university back in those days: in 1880, the entire college consisted of just one rector, five lecturers, and eight students. These students were all male; the first woman would not be admitted to the university until 1905. One of the students was the son of a butcher, another the son of a shipmaster, sailmaker, or shopkeeper: young men for whom a university education was by no means evident.

Their curriculum comprised three disciplines: Theology, Philosophy, and Arts. These were the three faculties that were the least expensive to operate, as they did not require labs or special tools and instruments. It also meant that the college lacked two faculties that were required for it to qualify as an official university: Mathematics and Physics, and Medicine. These were established only in 1930 and 1950, respectively. In order to still obtain an officially accredited qualification, the students sat two sets of examinations: one at Vrije Universiteit, and one at an officially recognised university such as the municipal university (the present-day University of Amsterdam/UvA).

The VU was not taken seriously in those early years, and in an attempt to change the minds of VU students, students from the municipal university had even taken to scrawling the phrase Laat alle hoop varen, gij die hier binnentreedt (‘Abandon hope all ye who enter here’) on the facade of the Scottish Missionary Church, right above the entrance; a reference to Dante’s Gates of Hell.

The Vrije Universiteit used this building during the first few years of its existence, until the opportunity arose to acquire the building on 162 Keizersgracht. It was an opportune time for the Vrije Universiteit to be vacating the church building, as the front of the building bore an inscription that some members of the Jewish community residing on the other side of the River Amstel found offensive: the command Predikt het evangelie aan alle creaturen (‘Preach the Gospel to Every Creature’) was written in large print across the building’s facade.

Location: Scottish Missionary Church

Preview of the In verzet en vol vertrouwen – de VU in de Tweede Wereldoorlog (‘Resistance Full of Confidence – the Vrije Universiteit during World War II’) city walk

Refuge and resistance

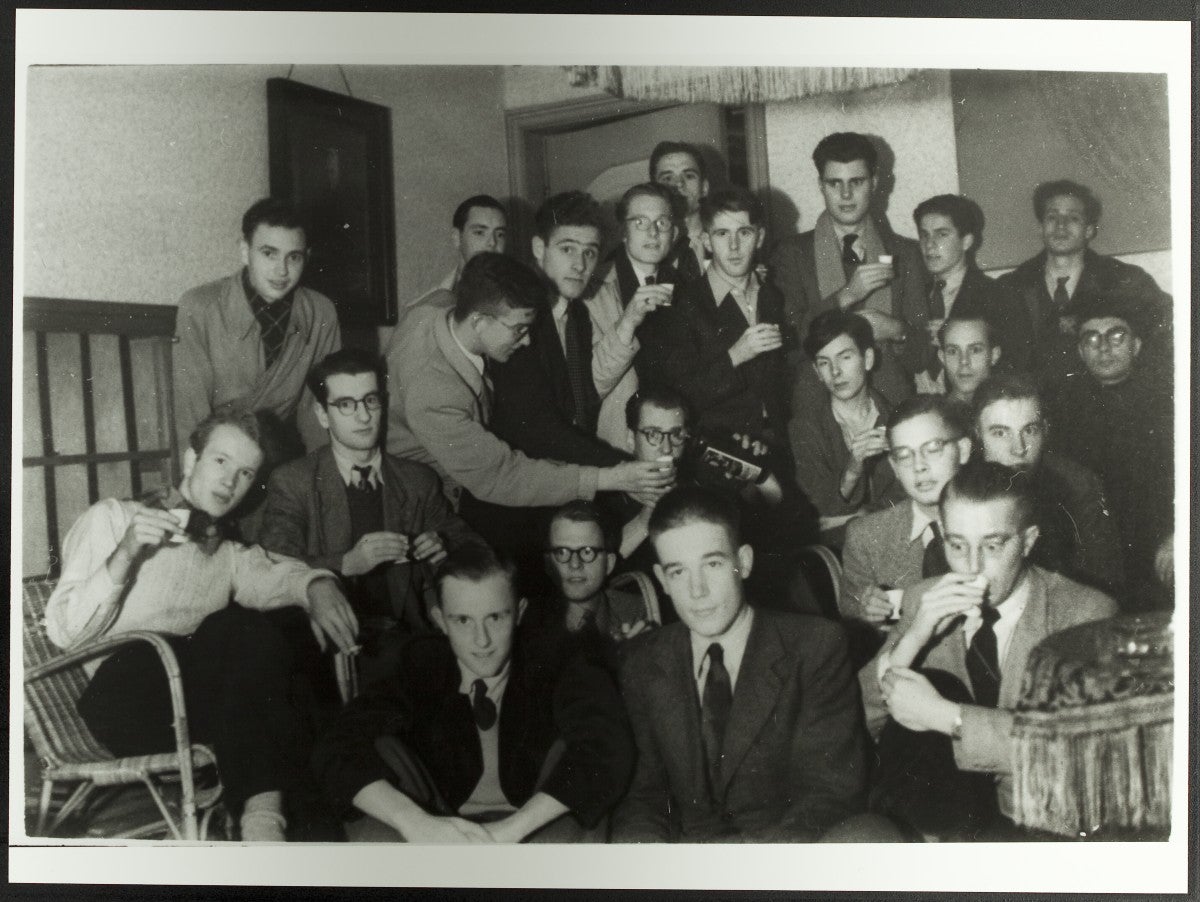

The physics and chemistry laboratory on Lairessestraat and the former Valeriuskliniek (a psychiatric hospital located right around the corner) were two major sites of the Dutch Resistance. In the summer of 1942, VU lecturer Jan Coops and two of his students began forging identity cards. In the chemistry lab, Coops even developed a technique to remove the letter J from the ID cards of Jewish citizens.

After the university closed its doors, a number of students took to hiding in its buildings to avoid having to be sent into forced labour in Germany, often posing as lab workers. Many of these fugitives ended up becoming active members of the Resistance themselves. Female students Rie Brouwer and Trui Koning were exposed to less risk when walking down the street than their male counterparts, as only men were sent to Germany. They exploited this advantage by smuggling ration stamps, identity cards, food or weapons, hiding these items underneath their clothes.

Being involved in the resistance from their lab base was not without risk: the German Gasschutzschule would be built right beneath the lab, on the first floor, where Nazi soldiers were trained to respond to gas attacks.

An underground hallway connected the lab to the older Valeriuskliniek, the psychiatric hospital that has since been demolished. Jewish people hiding from the Nazis were housed in the clinic from 1941 onward. It also served as a meeting place for the members of the secret College van Vertrouwensmannen (Board of Trustees), since the Germans were not likely to raid a hospital, not least for fear of contracting infectious diseases.

Courtesy of former VU Professor Van der Horst, who was the clinic’s director during those years, we know that the Vrije Universiteit discriminated against Jews in its hiring practices prior to the war. Van der Horst wanted to hire Edith Jüdell, a Jewish refugee from Germany, which was permitted only in exceptional circumstances. In February 1941, Jüdell was the only Jewish member of staff at the University to be fired from her position on the orders of the German occupiers. She died in a transit camp in Barneveld, Gelderland province.

Location: 176 De Lairessestraat & Valeriuskliniek

Those of you who are interested can listen to the full stories in the Dutch-language podcast. The accompanying walking guide (including two walking maps) provides additional information on the individuals and sites featured in both walks. Further information about where to find the podcast and obtain a copy of the walking guide will be available from early June on the Kuyper Week website.